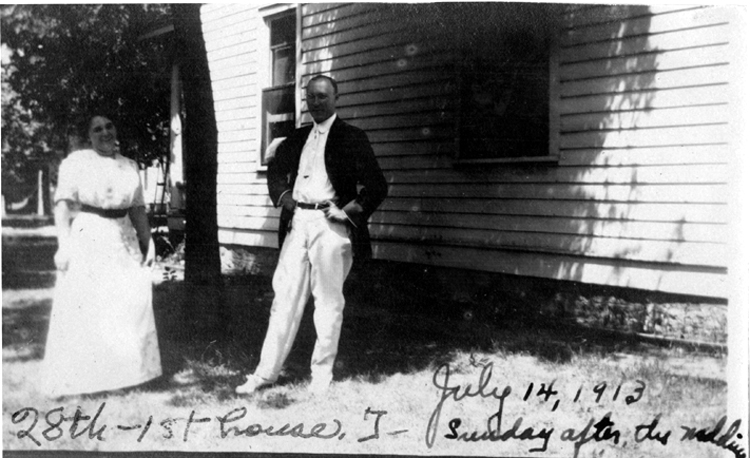

A certain eccentricity ran among the three closest sisters of my grandmother’s family, Nell, Sue and Evelyn, and quirky stories followed each of them through their lives. In her one room school in the 1890s, on the Illinois prairie, Nell developed a taste for mischief and a discerning eye for the absurd. She enjoyed watching the big farm boys standing before the class in their coveralls, red-faced and wretched as they stumbled through their declamations of “The Angel Wrote and Vanished” with full hand gestures. Later, on winter days when the teacher might be called from the room, the same boys gleefully clomped in a circle around the potbellied stove in their hobnailed boots, shaking the stovepipe down to the floor so class would have to be let out. At home, Nell’s brothers stuck her overdone biscuits in a row on the picket fence for everyone to see, her sister Sue dangled a daring, naked leg down through a stovepipe hole in the ceiling of the room where her prim older sister sat with a beau, and when William Jennings Bryan came to town, Nell and Susie found the silk top hat of the Great Orator unguarded in the foyer of the hall where he was speaking and poured a pitcher of water into it. Later they moved to Lincoln, her father turned from wagon making to house framing, and Nell met her future husband on the stairs between classes at Lincoln High. He was a tall Pennsylvania Dutch kid, a football player, wanting to ask her to a dance – but he bobbled the question so it came out, “Are you going to the dance?” to which Nell mercilessly responded, “No, are you?”

Walter Benjamin’s angel of history kept his face fixed to the past: “Where we perceive a chain of events,” Benjamin writes, “he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage on wreckage.” The storm bringing this wreck to him is “what we call progress.” Any chronicler from the polite middle classes faces this problem, of seeing past the sweet screen of the pastoral and the family anecdote to assess the catastrophic – in this case of not only the outer but the inner history, the genealogy of bitterness that could keep coiling through the supposedly Meredith Willson-ized lives of this Midwestern clan.

(from Chapter 4, “Keeper of the Partial”)

Wonderful writing, Neal.

Thanks so much, Allan – love to see you here. Take care, N