Neal is proud to announce the completion of a new manuscript, a memoir of the Camp Fire, November 8, 2018, that turned the foothill towns of Paradise, Magalia, and Concow into ruins – 27,000 people made homeless in 4 hours.

The book is titled SCOTTWOOD BLUE, Reflections on a California Wildfire, a memoir in ten chapters, each a separate essay on a theme of the fire – evacuation, global warming, native history, Paradise life before the fire, recovery, and more.

Below you’ll find the opening pages of the book as an introduction: cover, photos, table of contents, and the first chapter, “A Hundred Yards.”

Neal Snidow

with photos by the author

2024

Chapters

1. A Hundred Yards

2. Straw

3. Pulga

4. Smoke

5. Mantel

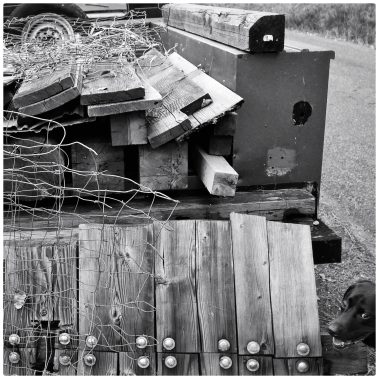

6. Dogs

7. Routes

8. Flails

9. Day Lighting

10. Scottwood Blue

For Deb, and for Caitlin who grew up there

Dedicated to all victims and survivors of the Camp Fire, Paradise CA, November 8, 2018.

This book has been informed by research from a variety of sources, particularly Mark Arax, Gone, The California Sunday

Magazine, July 31, 2019; Carle, David, Introduction to Fire in California, University of California Press, 2021; Fire in

Paradise, An American Tragedy, Alistair Gee and Dani Anguiano, Norton, 2020; Paradise: One Town’s Struggle to Survive

an American Wildfire, Lizzie Johnson, Crown Publishing, 2021; Ron Schwager and Phil Midling, The California Camp Fire:

Reflections and Remnants, 2021; Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag, Picador, 2003.

Also many thanks to friends and acquaintances who have shared their experiences with me so frankly over the years

since the fire. Any factual errors in the text are mine alone.

Your castle is surprised.

Macbeth

1. A Hundred Yards

What happened was that our town burned down. Not really the town we lived in, but the nearest town, even as the town we lived in also burned, but not our street. Our street was and still is intact in the foothills of the southern Cascade Range in Northern California, a wildland-urban intermix, east of Interstate 5 and Highway 99, about 2700 feet in elevation in a place called Magalia, an unlikely and genteel name from the 19th century that guidebooks dutifully report as meaning “cottages” in Latin. Our street is in a hamlet, a passing into history place known as Nimshew, now really only a road sign for some reason still given geographical authority by the county. Nimshew was once a First Nations place of course, Maidu most likely, the word apparently meaning “near water” in the straightforward way of landscape naming in native communities, or at least those we know about, or think we know about.

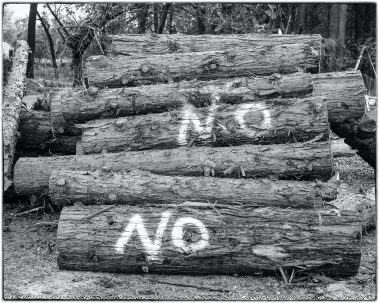

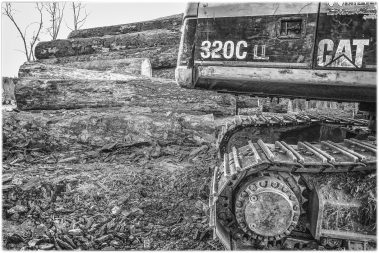

One of Magalia’s original names was Dog Town, a more suitable name smelling of the gold rush and the decades of extraction, or plunder, generally from 1850 on—pelts, gold, timber, gravel, turpentine, then mostly trees, for timber, railroad ties and trestles, and then toothpicks and matches from the practice of clear cutting on the mountainsides near Stirling City once the biggest trees were gone, which continues into the present day. Although Nimshew Road, and our cul de sac opening from it did not burn, a lot of Magalia did, two miles or so closer to Paradise, 3000 structures, almost all homes—once we had evacuated the morning of the fire, staying away and hearing little for two weeks or so while crews, almost 5000 firefighters, kept at the fire, we only knew from rumors our street hadn’t burned, and so worried like everyone else.

What would happen was that someone who knew a county deputy who had driven through the neighborhood on patrol would get a text from him so then text a friend who then Facebooked that at least on that pass everything still looked all right except that there was “a lot of ash,” and of course your door was locked, you hoped you’d remembered, but this was still an opportunity for robbers, looters as everyone knew, those who hadn’t evacuated but had hid out in the many nooks and sheds and overlooked spots on our remote ridge. The idea would be to gain something of value left lying around of course, guns or a generator or lap top or a quickly severed catalytic converter from a car left outside, in the low end economy of the foothills whatever could be most easily exchanged for meth generally, although a big item like a Costco generator would likely keep someone in liquor, speed and even a bit of rent or traveling money. With this possibility as well as fire, we evacuees were tense for several days while the fire line hovered near our road, feinting left, then right, juking up the chimneys and swales runneling the canyon walls of the upper ridge. But when all was done, there was no major looting and no fire on our street.

Paradise was the town that really burned, however, 95% of its structures destroyed, a couple of miles west of the market and post office and gas station that was Magalia’s center point. Paradise was also a nineteenth century place and name, some gold in the 1800s but not quite the rush that had stirred up in Dogtown where a 54-pound nugget was found in 1859.

Paradise was timber, ranching, and at its bucolic peak, apple orchards, and then a minimally zoned, inexpensive bedroom sort of community to the more bustling ag and college town of Chico 8 miles west on the floor of the Northern Sacramento valley, at the confluence of the Sacramento River and Butte Creek. Was Paradise named for a bar, “Pair O Dice”, or by ranchers coming up the hill out of the valley summer heat?

A prodigious heat always, the men resting under a copse of full grown Ponderosa pines native to the elevation, a breeze in their blessed shade, and the rancher—Mark Arax of California Sunday Magazine and expert in all things California believes it was a William Leonard— pronouncing, “Boys, this is paradise!” and the name sticking.

At any rate, on November 8, 2018, the town burned, almost all of it in four hours, most of its structures, homes and businesses, leaving 27,000 citizens homeless. The fire moved very quickly under blustery winds and drought conditions—moving the equivalent for several hours of at least a football field a second, that is a one hundred yard patch of ground, of red earth, of swales choked with manzanita, of canyon sides of rock and yellow grass, of rising and falling land with oak trees and unthinned conifers growing bunched civil war style, Battle of the Wilderness impenetrable, some places thicketed for acres shagged with dried cow peas, broom, chemise, Russian thistle, then yards, sheds, neighborhoods, trailer parks, schools, a Safeway, a hospital, people watching morning television, then watching out the window, then moving fast toward their cars, old people in cottages built in the 30s or 40s or 50s, small porches bracketed in madrones and wild grape at the end of an old gravel and dust driveway, one with a bend or two in it, lined with buckwheat, mullein, and deer grass, wind whipping pine needles, first a pattering hail of these and then of needles alight, burning onto the roofs with the sound of hail, the older people in little houses and trailers rising past their bedside table, water glass and pill sorter, smelling something, hearing a roar, and the fire under its regime of wind blowing horizontal moving another hundred yards over this terrain in a single second. And then another.

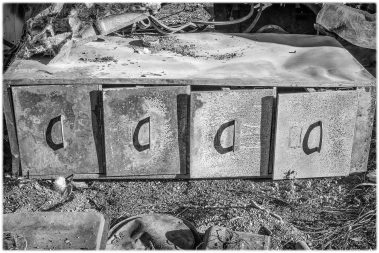

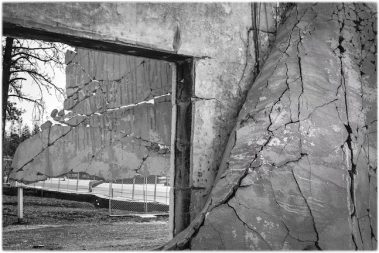

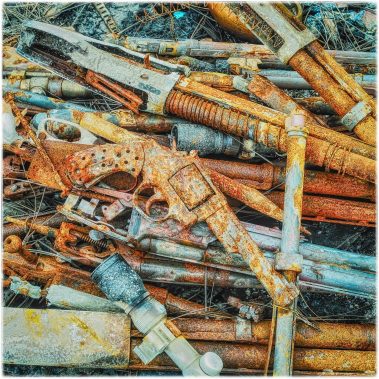

rental housing, Paradise

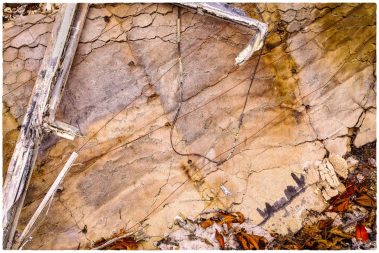

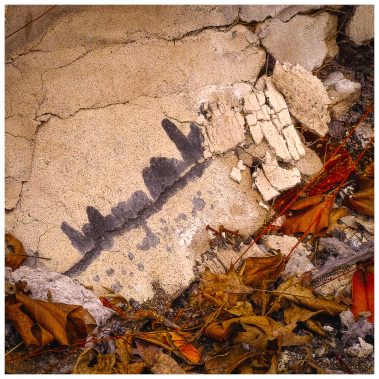

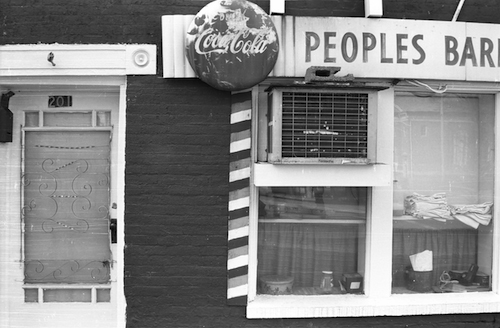

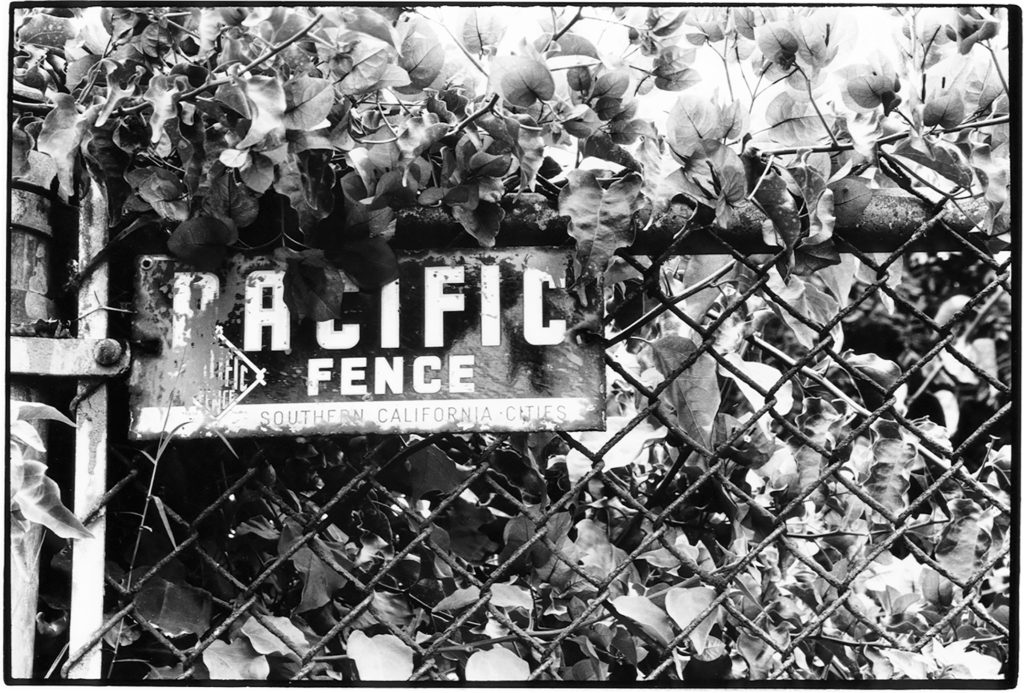

One of the book’s additional landmarks is its photography, images Neal made in the winter of 2019, documenting the poignant and elegant scenes left in the burn zone. Here are sample photographs.

As a last example of the writing in Scottwood Blue, Neal invites you to read the opening paragraph of chapter 8, “The Flails.” Thank you visiting the site! Feel free to leave comments in the Contact feature.

In David and Tamara’s yard a trencher of Ponderosa bark aflame and spinning flies past out of the smoke, striking and igniting the wisteria, the manzanita, grey pines, raked piles of needles along the top of the driveway, then the house itself; and as the fire is no longer new here but circling back in some way, what also flies by is a piece of someone else’s burned home, a fragment of board and batt, lapstrake, cabin wall, cedar mansion kit home, stucco, chicken wire and shreds of flaming one by six, pieces of barns, trailers, a one foot square of presswood veneer spinning sideways, wobbling out of the dark, its grooves 12 inches on center aflame with a patch of pink insulation and panel shard to the meltable but not strictly flammable metal skin of the mobile home from which it’s been ripped. In the wind before it rises to its loudest level, the locomotive roar of the canyon-filling fire, there’s a quieter moment as it’s coming, heralding the katabasis on its way, the voyage through the underworld for everyone here today, sussurus, coruscation, and excoriation; the fire’s boss and motto could read whisper, shine, flay.

Praise for Vista Del Mar, a memoir of the ordinary

a magnificent memoir…graced by a riveting narrative power, and by nuanced, deeply revelatory, and moving insights

Maurya Simon, author of The Wilderness: New and Selected Poems, 1980-2016

…beautiful prose – better than many far more celebrated writers….handles personal subject matter with perfect unsentimentality and tact. What really stood out was a resonant poignancy, “emptiness” in the positive Buddhist sense, in suburban things so often dismissed as tacky…that, and the sense of “soul work” in recovering the things of one’s past.

Alan Williamson, author of Westernness: A Meditation

…joins the company of “self-work,” deep acts of memory….The book stands alongside the work of D J Waldie’s Holy Land, Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem, and the profound My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard.

Jack Shoemaker, Counterpoint Press

Flawless. A perfect recreation of a Southern California post WW II childhood.

Jane Vandenburgh, author of A Pocket History of Sex in the Twentieth Century

Neal writes memoir and photographs,

sometimes together

so that during the writing,

images harmonize with words

as accompaniment, descant, or second line

As John Berger says, “There is never a single approach to something remembered.”

Neal hopes you enjoy these examples – feel free to contact him with questions!